Transcript: Accredited LOPD symposium

Prof. Schoser, Dr. Mozaffar, and Dr. Kishnani

Symposium recorded February 2025. All transcripts are created from symposium footage and directly reflect the content of the symposium at the time. The content is that of the speakers and is not adjusted by Medthority.

- We have here today a very esteemed team of speakers. So with me, I will introduce them a bit later on. We will work up here a bit things on Pompe disease, elevating care through patients' insights. And here the faculty, of course, besides me, and he will be the first speaker is Tahseen Mozaffar. He's the chief of the Division of Neuromuscular Disease at the University of California, Irvine. So he is really the true matador here from California with us. And beside him is Priya Kishnani. I think I don't need to introduce her. We all know her so well. She's in the Division of Medical Genetics at Duke University in Northern Carolina. And since so many years, one of the key experts in the field of Pompe disease. And she will give also us today her insights on our topic. So we take care a bit about patients living with Pompe disease, and we want to touch elements of the disease, they're normally not covered.

So it's more about wellbeing, quality of life. It's about how to manage pain, how to manage central nervous system, gastrointestinal or urine tract parts of the disease. So therefore, a lot of interesting topics they are normally not covered, and hope you'll have a good takeaway later on after this hour. And without further ado, Tahseen, stage is yours. - Thank you, Benedikt. It's a real pleasure to come back to San Diego and talk about Pompe disease. And we have the pleasure of having a fairly large Pompe clinic and a Pompe programme. So some of the stuff I'll show you is work from our centre as well. So the learning objectives, as Benedikt mentioned, is to understand the key challenges that are experienced by patients with LOPD and their caregivers.

What are some of the strategies for holistic diagnosis and management? And how do we improve the quality of life and take care of some of the challenges, medical challenges that we face with Pompe disease? So these are my disclosures. I have a very active clinical trials unit, so we get research support from a number of industry sponsors, but also advise a number of industry sponsors. So the bigger challenge with Pompe is that one, it's a very slow, progressive, slow onset disease. It takes years for the symptoms to really manifest to the point that the patients may realise there's something going on. And I'm particularly talking about late onset Pompe disease. Infantile Pompe disease is a little bit more catastrophic, so you get picked up earlier. But late onset obviously is a little bit more. So there is an inherent delay in diagnosis. A lot of the symptoms and signs of disease are overlapping with some of the other muscle diseases. So they overlap with muscular dystrophies, especially limb girdle muscular dystrophy. They overlap with polymyositis, if there's such a thing as polymyositis.

I'm not a big believer in it. But other metabolic muscle conditions, et cetera. So it's not unusual for these patients to get misdiagnosed. Now a lot of them also have back pain because of paraspinal muscle wasting, so they get shunted off to orthopaedic clinic, and then they can shunted to liver disease clinic because they have elevated transaminases, even though transaminases can come from the muscle. Some of the symptoms are non-specific, so they get a lot of fatigue. They get sleep disordered breathing, et cetera, which may cause issues there. And generally, there is a lack of awareness amongst general practitioners, and I can venture and say that even amongst the neurologists, and I'm a neurologist. But most general neurologists probably have never seen Pompe, they've never come across a patient with Pompe. So there is generally a lack of awareness for diagnosing Pompe or how to diagnose Pompe in that sense. So I'm gonna start with this case. This was one of the first diagnoses of Pompe that I made at Irvine. This is somebody who had, was in his almost 50s when he first came to see me.

He had almost a 20 year history or 30 year history of proximal lower extremity weakness, and his weakness started when he was 25, and had difficulty getting up from the floor and going upstairs. So his lower extremities were the primary issue. And then somewhere around 35 years of age, about 10 years into the muscle weakness, he developed shortness of breath upon exertion. His arms were surprisingly not as affected, which is not unusual in Pompe. Pompe, again, like limb girdle muscular dystrophies tends to affect the hip flexor muscles way more than shoulder flexor muscles on that. There was no cramps or muscle spasms. And he was thought to have limb girdle muscular dystrophy because his younger brother who lived in Vegas had already been diagnosed as limb girdle muscular dystrophy. So the assumption was that he probably has the same disease that his brother has. Now, when I examined him, he had proximal muscle weakness, and by the time I examined him, he did have some upper extremity weakness, primarily in this infraspinatus muscles, so the scapular muscles, which is very early involved in Pompe. But he also had axial muscle atrophy and had bilateral scapular winging as well. His walking was definitely affected, waddling. No sensory symptoms.

And the clue to his diagnosis was in his pulmonary function. So in our clinic, we are lucky that we have a full-time respiratory therapist and we do forced vital capacity in both sitting and supine position every visit. And we were able to detect a 14 point drop, a 14% drop in his FEC. Even though his erect FEC, sitting FEC was normal, he dropped by about 14% going supine, suggesting that his diaphragms were affected. And that was the first clue that we had that we are dealing possibly with Pompe. To go along with that, his inspiratory pressure was minus 52, which is quite low as well. So we sent off, back in those days, we could do free enzyme assay. We sent off his blood to Duke. We saw that it was incredibly low. The lower limit of normal was around four. He was 1.45, so clearly was in the deficiency range. And we did the genetic mutation and he had two mutation, one was the common leaky splice site variant, and the other was a little bit more aggressive mutation. So his diagnosis of late onset Pompe disease, and now mind you, this is 25 years after he developed symptoms was confirmed. And based on his diagnosis, his younger brother revisited with his neurologist and was confirmed to have Pompe as well. So currently, this gentleman has been on enzyme replacement therapy since 2006.

He was one of the original patients in the ACTUS gene therapy trial. Unfortunately, he had to go back on the enzyme replacement after two years of gene therapy trial, and now develops significant camptocormia. So he has a bent spine when he walks, and also has failure to thrive or unintended weight loss that we are trying to manage at this point. So, I'm just gonna go over an online survey of people with LOPD that was conducted as part of this session. There were 20 subjects that, 20 individuals that answered this. 50% of them were based in the US, 50% were based on the UK, and half of them were male, half of them were females, and the mean age was around 47.7 years. Now, 60% of them were involved in patient advocacy, which is great because we need more people sort of advocating and pushing for more reforms. Fairly educated bunch, and fairly sort of even in terms of income and family income as well. Now, the age of onset for the first LOPD symptoms were quite variable. Some of them had it very early, between zero and 12 years. Some of them had in their teenage years, between 13 and 18. And then a larger number was between 19 and 39, and then some were even later. They weren't diagnosed till their 50s and 60s. So the average age of diagnosis was about 36 and 36.3.

But if you look at the right side column, if you look at when the diagnosis was made compared to when the age of onset of symptoms was, there was a considerable delay. So 50% of the patients had a delay of greater than 10 years to establish a diagnosis, and then 20% of patients had a diagnostic delay of over 20 years, which again, in this day and age for a treatable condition is almost unacceptable. If you ask the patient what they think was the reason why they were not diagnosed earlier, and I think a lot of them pointed out that they felt like their primary care physician or healthcare providers were not aware of this rare disease. This is a rare disease. Again, we, at least in academic institutions, we make an effort to educate our trainees, but it's not done in other specialties outside neurology or maybe genetics. So again, a lot of these individuals don't have knowledge of it. 75% of these individuals that were surveyed noted that they were misdiagnosed initially, and 65% said that there is limited availability. And I will tell you about a study that we are doing right now, and a number of these patients are from Missouri. And in rural Missouri, there is a tremendous healthcare shortage. So physicians are scarce and the physicians that are there don't have the knowledge, plus they don't have the time. But there's also racial biases as well that we have to deal with. And we're trying to address all of those in a manuscript that I'm writing right now.

This delay clearly impacted their daily functioning. It affected their breathing, so by the time they got diagnosed, their breathing was already affected. This could have been prevented and this could have been delayed. And we don't think about pain in Pompe, but pain in Pompe actually is quite common and something that needs to be addressed as well. Then, however, despite all of that, when these patients were started on treatment, most of them did not find any additional discomfort with treatment and were satisfied with the treatment overall. So if you look at the pie chart, 50% had no discomfort, 40% had mild discomfort, and 10% had moderate discomfort on that. So as I said, we are in the process of writing a manuscript. This is a multicenter study from eight centres in the US, and we essentially focused on patients with diagnosed Pompe, and we went back and see how many of them were misdiagnosed initially and that.

So we found for 54 patients, the three commonest diagnoses were liver dysfunction, including doing a liver biopsy on them, back problems or back spine problems, and the third was polymyositis, which is a rheumatological condition. And some of these patients were poisoned with immunosuppressive. The mean age of onset for symptoms was about 30 years. The mean age at initial diagnosis, and that may not be the correct diagnosis, was about 38 years. And the mean age at first diagnosis of Pompe was about 42. So luckily the delay from the initial diagnosis to Pompe diagnosis wasn't bad. But if you see there was a 12.7 year delay in diagnosis that this person had something. And a lot of factors as I mentioned play into it. I think our care in the rural setting is not the same as in the care in the urban setting. There are inherent racial biases, et cetera, that we have to look into as well. And then there are training biases. If somebody comes in with elevated transaminases, the assumption is it's coming from the liver and they get referred to a liver disease specialist.

If they come in with weakness and high CK, it's assumed that they have polymyositis and the patient gets referred to a rheumatologist. So again, there are challenges that we have to face at this point. So the take home message is there is significant delay of diagnosis in late onset Pompe disease, and it's driven by a diverse range of factors, including awareness amongst medical professionals and symptoms overlapping with other conditions. This creates a significant burden for people living with late onset Pompe disease, and these delays can be substantial, with an average duration of greater than 10 years from symptom onset. So lived experiences of people with LOPD really offer us valuable insights, and hopefully this will be, can be leveraged into a more improved, a better diagnosis. Thank you. - All right, thank you, Tahseen, for this wonderful introduction to the disease. I will continue, I will give you a bit more insight on the topic he raised already on pain and also wellbeing in adults living with Pompe disease. And we have this handful of new datas, also, I will continue with this part. Here are my disclosures, similar to Tahseen, I also was one of the leads in the phase three studies PROPEL and COMET. So therefore what I'd like to introduce you is something that I call the Pompe Gestalt.

So what is gestalt? It's a German word, and I'm German, of course, but it's a philosophic term. Gestalt means more than phenotype, so the complexity of a disease is different to just what we call phenotype. So gestalt is something you can easily catch normally. So, a bird watcher, with the shade of a bird, he already knows this is the whatever type, eagle or whatever you consider this. And even if you're a whale watcher, by the waft of the whale, you can name them and give them really an identity. And that's something what you need to do if you're doing gestalt approach to disease, and what we are doing here is in a way similar. If you look at the multisystemic events, what happened in a person living with Pompe disease, it's quite a bit, and we mostly care about neuromuscular and we leave out a lot of the other things. But you will learn today and especially later on in the talk of Priya that there are a lot of systems are affected, and we don't take care about them, but there's a need to manage this in future better. And of course you know about the general burden of the disease, this is really still high.

So we have proximal and axial weakness in mostly all of them, and still if the advance stages of the disease, we have a lot of people on the wheelchair and they need supportive respiratory devices. And even then without all this, there's also the most likely difficulty for emulating, and even fine and gross motor function skills are going down in a way. And still the topic no one is really talking about is that the mortality in our even now long-term treated cohort is still high. So this is not solved, it's not the normal way in living this. And we did a study, this is a long time ago already, so in 2017 where we looked at the substantial humanistic burden of the disease, and here you can see that a lot of things are most important. So it's motor disability, of course, it's the respiratory part, cardio-pulmonary function. But then all the more soft things coming in, so it's fatigue, it's sleep disturbance, it's pain and anxiety and all these type of things.

And so therefore there's a strong relation of the burden and among the humanistic burden and parameters of the clinical progression of the disease, and also this is something we need to take care. To confront you a bit more on this, so what is really the patient's perception of this? So, really turning around, not having always the doctor's head on, so really looking what is the perception of the patient. And here is a super busy slide, so we can't go in details, but this gives you really some direct and general impacts of the disease for the patients living with the disease. And you have parts of mobility, psychological parts but also other things, problems that work studying financial difficulties coming up here. So there's a lot of these things we don't talk normally about, and things like just having a meal outside and go for dinner is not always that easy for the patients. And so therefore compared to the general population, we have a three time lower situation in the quality of life, and also with some of the parameters we see, definitely that there is a difference to the normal population in the untreated, but still this turns into treated population as well.

So therefore there's a lot of things we don't cover. And pain is one of them. So that's an old study we did back in 2013, so it's 12 years old, but that was one of the first summaries, and Priya did another study on this and it backed up very nicely, that in Germany and the Netherlands, we have up to 50% of the patient do perceive any type of pain in different parts of the body. And this is one of the top drivers to decline the quality of life, so therefore this is something we should look at this. So therefore this talk will read this time focus on the peripheral and autonomic nervous system, and also in part of the central nervous system because we learned that there's more to go for. So, how can we explore this and the nature of this? And I'd like to remind you that in the Pompe Gestalt, it's really the brain damage that also may impair emotional functions. And we know that there's still an ongoing, even the late onsets are ongoing glycogen accumulation in the central and peripheral nervous system. And of course, we have types of neuronal dysfunction and vascular pathology. So we have this from the old autoptic cases, we know it pretty well.

And this is under esteemed, so we care about metabolism in muscle and try to fix that, and we completely neglect that there's also a brain topic in the disease, not on the very high level and patient by patient differently. That's our trouble, our issue in it, but it's still there. And this all together impacts, of course, the cognitive and emotional function in the LOPDs, and there might be, so this is given in small studies. So far, we need to do more work on this, the executive function impairments is there. We have the topic of anxiety and depression in the patients, high levels of pain and fatigue, and also moderately to high impact of impairment in the cognition in some of the patients. And if we look here for the psychological and emotional support of our patients, so what are we doing here? Are we going just prescribing the enzyme and leave them perhaps with a prescription of physiotherapy?

And if you look here, this is a glimpse into the patient's side, you see we are doing not well. So up to two thirds or even up go to 80% say, well, I don't have really the best feedback perhaps and adequate response to all my questions I have. So there's room to improve for us to do more here for our patients. And you look at the peripheral nervous system also there is some glycogen accumulation, and that contributes in parts to the pain topic. We did a study for small fibre neuropathy and it was clear cut there's also lysosomal storage and glycogen buildup in those. And we have this situation, some of the patient, not in all, but we did not really thoughtful do this in all patients, looking for burning feet syndrome, so restless leg syndrome could be something. And we have some neuropathic pain traits in the extremities of the patient. So the other thing, hardly touched because we also ignore this is autonomic nerve system function. So there's abnormal sweating in the patients, something we hardly consider because then it could be a 50-year-old woman, it could be a 60-year-old man.

So there could be a hormonal influence and things like that, or it's just normal by ageing. But parts of this is not normal. Parts of this is just a new facet of Pompe disease and we don't go for it. And gastrointestinal dysfunction, I think Priya will cover this very well later on, so this is very important, also neglected, and also not on uptake, because some of us are metabolic specialists. I'm a neurologist, so why do I care about urine tract? I don't have the education for this, but if we treat a multisystemic disease, so we need to go for this and look for help even for us, so therefore this is super important. And we all know if you look at the registry data, the data we have enhanced for all the clinical trials that of course the musculoskeletal system and the bone involvement is there, and of course, pain is related also to this. We have just a case, Tahseen presented, we have the bent spine, rigid spine syndrome in a subgroup of patients, and we have scoliosis in quite a lot of our patients. And if you look at all the wheelchair bound patient, there's nearly each and everyone has a scoliosis. So this is also something we did not cover well, and we need to do more on this, and scoliosis in one of the old studies we did was up to a third of the patients. But if you look at the aged population, you see it nearly in each and everyone.

And of course there's the topic, if your muscle is weak then osteopenia and osteoporosis is something that's coming up, and also we need to take care for this as well. So we were interested and this short glimpse here we did for this was also a cross-sectional survey. In many patients with LOPD, receiving some symptomatic pain treatment. And a lot of them reported that they take non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, or they take paracetamol, or even quite a bit, and that might over here in the US even be more, taking opiates. So, there's a lot of different things, and many of them do conceive also physical therapy alone or the combination of things. So, and still in more advanced stages where they are more moderate to severe affected by the disease, the pain level goes up. It's not going down, it's going up definitely. And I had to talk to one of our patients over here, you heard yesterday if you were there, and she perceived just by coming over here, flying 12 hours, definitely the main topic for her was fatigue and pain and that's it. It was not a weakness that was so in front, it was really the fatigue and pain what was a high topic in here.

We did some interesting studies in this. So there was really, is physiotherapy something we can help? Unfortunately so far, we did only this in a clinical trial for our standardised assessment in more mild affected patients. So we don't know how good is really physiotherapy and all what we can do on this side in the more affected patients. But still there was already the outcome what we did all with the different methods, and I go to this directly, that in the most of the patients with more exercise, any type of whatever you can do and expose on them and what they can afford to do. So this is also something you need to learn. So, what is your border zone for having not more pain under training situations? And how can you widen this zone for your fitness? It's very important but this stabilise also the pain, so it's really an element not to be neglected is a good health for reduced pain with having physiotherapy.

And one of the unmet needs is really to understand better the symptomatic pain. So what is really, of course, I told you a bit about this, but this is not very well investigated. But here in the 20 patients in this survey we have here from the UK and from the US, they say, well, most of my pain is not really well managed. So there's some help for this, but it was not really done very well, and we need to look into this in more detail what could be a better pain relief system here. And regarding how patients manage their pain, so some of them said, well, we use lifestyle, any type of things we change that, and I said, 60% we use pharmacological treatments, and physiotherapy is coming up, and even some different types of device what you could do and also then water and hydrotherapy was there included. So there's quite a bit of information, but of course, no systematic review on the situation, and especially no studies done.

So if we wanna understand treatment, so we need to understand really the discomfort and also the decisions for this. So understanding that 90% of the patients said they have a good understanding of the disease and the treatment for the disease, but they have not always a good satisfied answer to all their questions they have treatment wise. And in 50%, they had no treatment related discomfort, and 40 had a mild discomfort, and 10 only a moderate discomfort. And the decisions were mostly made by the patients alone. And this is a key element I'd like to touch here a bit. We need to come much more to the concept of shared decisions. You need to listen really as a doctor to your patient and then try to find out what is really this thing perfectly fitting to the one sitting in front of me, because it will be completely a different situation if the next one is coming in. So they all have really the individualised situations, and we need to take that up and then give the feedback and give the understanding why they should perhaps treat their pain differently as they did it before, and then they would have a solution for their pain conditions.

So this is important. So my key take home here is that we need to look more for pain and emotion. This is really a hot topic for the patient. It's always coming up in the IPA survey we have yearly from the Erasmus and from the MDA group together. So this is important. Our current understanding is still a multi-systemic perspective, but not well addressed in all details. And the current clinical management is based for sure on the ERT, the pain topic is better improved, but we need to do more systematic studies on the pain treatment in these patients. And of course, this all is based up in the emotional perception and a shared decision concept we need to go for. So therefore more work to do. It's not solved all with our current three prescribable ERTs. We need to come along with new ideas how to manage all this better. And by this, I close, and I'm happy that Priya will now add a lot of extra facets to this disease.

Thank you. - Good evening everyone. Can you hear me? So I'm going to try and talk about, so first of all these are my disclosures. And the way we have approached medicine in an academic setting is the bench to bedside, and more importantly, the bedside to bench approach, and the crosstalk between the two to try and bridge the gap and try and find therapeutic strategies and better understanding what is going on with our patients with rare diseases. And so with that, I also want to point out that every time a patient comes to the clinic, there is something to be learnt, and careful listening has been the art form for medicine, but for me, it has really been a humbling experience. And I'm gonna start with two case vignettes. So patient one was 49 years old, he had an eight year history of late onset Pompe disease, and he complained about not being able to lay supine without the use of BiPAP. He was using a cane, he was living alone, and he acknowledged that he was unable to go from supine to sit or to stand. He also reported in clinic a history of falling in the bathtub with the inability to stand. And he was found three hours later by a caregiver, you know, who had come for those few hours of the day. PFTs were done, of course, and he clearly had the upright forced vital capacity, which was 34%, which I think for this audience now, you can tell is extremely low. But the importance of getting the supine forced vital capacity was really informative here, it was 10%. Talk to the patient about this, explain to him this is a problem.

What was the real outcome? He was found deceased on the floor one week after his appointment with us. Patient number two, a 62-year-old female. She was morbidly obese. She was diagnosed with late onset Pompe at age 51. Was very excited because at that time, the initial clinical trial, she was gonna be the first patient actually on commercial treatment with IV l-glucosidase alpha. And what were her complaints? Again, frequent falls. She had called EMS several times. She had severe orthopnea, except in the upright position, so she often slept in that upright position. She declined to use BiPAP use. She was ambulating independently, so there was a false sense of security that I can get by. Her lung function test, the upright was 34%, no supine PTFs were done. Patient did not want to do it. What really happened, she was found deceased the day before, or I think it was the morning of the day she was coming for that first treatment of hers. She was found lying prone after an apartment fall. There was no anatomic cause of death on autopsy, which she did have. And so it really was a wake up call. We understand the pulmonary system and Pompe disease. We talk about many aspects. We know that there is respiratory compromise. We also know that patients can have a disproportionate involvement of skeletal muscle and diaphragmatic involvement. We also know that a primary cause of death in patients with Pompe disease can be pulmonary insufficiency. But I recognise that I had to make a change in how I was communicating the information to the patient. The role of lung function tests, or PFTs is clearly important, but is it really critical in some patients to get that supine PFT? Absolutely.

So if someone has a low upright forced vital capacity, I am actually insistent that they get it. And I think I do another thing. I have them lay down in clinic and I ask them, "Lay down and I'm gonna see how long you can last without finding it hard." It's really to let these patients know that they are vulnerable, and that we've got to do something to help them. Also talk about the importance of BiPAP or other ventilation. Expert pulmonologists, there are different ways by which you can find ways, an appropriate mask that fits, because it can be uncomfortable. And also regular assessments, especially for their lung function tests, even if they're mobile patients. And I think the key that it made for me in my clinical practise is the insistence of the medical alert, the life alert device, the fall alert devices, or just simply wearing an iWatch and having it connected, you know, so that if someone has a fall, that they can be attended to. So that was one personal experience. The second one was, as we've been taking, you know, detailed histories from patients, again, the focus on lower urinary tract system I have to admit really came because of listening to the patients. So some of them, you know, feel vulnerable, but they do talk, and I was told that there was a history of this urinary incontinence, a weak stream.

It was embarrassing for them to talk about it, but faecal incontinence, and that it was having a significant impact on the quality of life. And so our line of thinking at that time, these were in the early days, we knew of it as a skeletal muscle disease, a limb girdle muscle disease, one that involved the pulmonary system, but what does it really do to smooth muscle and other muscles? And so the question was, is there glycogen accumulation? And what is that really doing? So sometimes the way to do these kinds of sensitive topics is I think is through questionnaires, where the patient really doesn't have to converse with you about it, but it can be put in a questionnaire. And so the art I think to medicine is collaboration and recognising your own limitations, and so we collaborated with urology. And they have some very good, some very good questionnaires for lower urinary tract symptoms. And so we were able to enrol from our group at Duke, and we host an annual meeting, and so during those times it becomes, we try and attend to a question that has come up and try and get answers through the patients in this kind of manner.

So the questionnaire was done, and it was done for the incontinence impact, for the urogenital distress inventory, and then there was one which was called the American Urologic Association Symptom Score. And along with that, of course, we were getting the six minute walk test, other functional measures, and trying to see what we could glean from this. What we learned was actually that a large number of patients, more than two thirds actually had at least one lower urinary tract symptom, and that females had different complaints as compared to males. Incontinence, both urinary and faecal incontinence, was much more in females, and post void dribbling was really what we had gleaned now from males. And so with that, we tried to see is there an association with stage of disease progression? And clearly there was, I mean, those patients who had more difficulties, more advanced disease tended to have more increased symptoms.

And about 40% of patients really reported frustration, interference with their activities of daily living, and overall felt it was really problematic, not able to go to social settings and gatherings because of frequent urinary tract symptoms. So the key observations from this was that we learned that it does affect the lower urinary and the gastrointestinal tract, that this is often overlooked because of multifactorial causes and overlapping presentations. It's often not asked. Often the patient is embarrassed to bring it up. And as I pointed out, it can vary by anatomy. So for males, what we learned then through the mouse model is that there is much more involvement of the bulbospongiosus muscle, and of course we know prostate enlargement in males, and for women, it's more because of pelvic floor dysfunction. So what did we really do for clinical practise is we started asking these validated questionnaires, and the idea for it was not just to gather data, but now a multi-discipline approach, collaboration with urology, more importantly urogynecology, and with gastroenterology to help address quality of life for the patients.

So as we did that, I started recognising what about the children with Pompe disease? And do they have also urinary tract symptoms? And to do an exam in a child is sometimes easier, but even then it's kind of embarrassing, you know, to try and look at rectal sphincter and anal sphincter tone. But nonetheless, we had already got some clues into that, but we had not done a systematic study. So with that, the goal was now to incorporate this in the paediatric patients. And so we looked at 16 children with Pompe disease. We looked at infantile Pompe, and we looked at late onset Pompe. And then what we used was a bladder control symptom score. Now, I would not know this. Again, working with a paediatric urologist was the best way forward. And so we looked at this, and what we found out was this, about 40% of them had significant voiding dysfunction. Classic infantile had the highest scores in terms of the bladder control symptom score. And the common symptoms were daytime urinary incontinence, giggle incontinence, children laughing and they have this whole void of urine coming out.

Nighttime bedwetting, and, of course, also faecal incontinence. And what then started coming out was an embarrassment for sleepovers, et cetera. So trying to address this. And girls reported a higher rate of this lower urinary tract symptoms than boys, including more frequent urinary tract infections. And so this became like what can we do for next generation therapies? Are these kind of endpoints, are these kind of things we need to look into? And we did, and as we've started incorporating it, we've started asking these kind of questions to help us in better understanding disease response outside of the standard clinical trial endpoints which are done. And so from this, I also learned from some of my patients about diarrhoea, about bloating, about constipation. And many of them said that they were using medications like loperamide several times in a day to manage their symptoms. And so this again made us think, let's look at this and look at what the GI system, symptoms are and what is going on in these patients. And so we again did this quick look by asking, and we looked at the PROMIS questionnaire.

This is available free of cost, and there are GI symptom scales there. And we also started taking a very GI focused medical history. And what we learned was that nearly all patients were reporting gas, bloating, GERD, constipation, alternating with diarrhoea. And about 28% of them had very severe symptoms for certain domains. 82% reported no improvement in symptoms, despite prolonged use of enzyme therapy. And actually in six of them, we also uncovered that it was likely one of the infusion associated aspects of ERT because it was occurring within the 48 hours of the infusion, and as such, it was an infusion associated reaction, so to state. So what were the other medicines that were being used? Antacids, antidiarrheal agents, as I said, for loperamide, probiotics, CoQ10, bulking agents, stool softeners, laxatives, tincture of opium for severe GI discomfort.

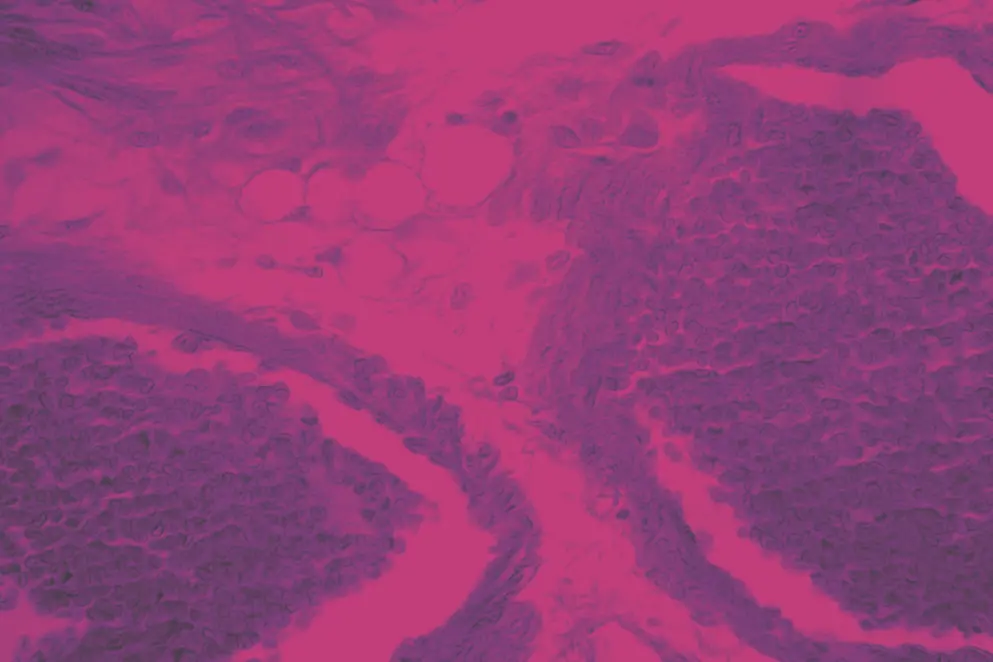

And really, we had missed a lot of this in what I feel, we have the luxury of an hour of time with our patients, but still this had been overlooked. And so I then said this is important and we need to look at this in the Pompe mouse model, try and understand what is going on. And at this point, we were also noting tongue weakness in patients with Pompe disease, and this was in collaboration with our colleagues from Argentina where we first described this. And then looking at the Pompe mouse, you can see that there is glycogen, and once again, I don't want to send alarm bells. It doesn't mean because there's glycogen that you're necessarily gonna have a symptom. But what we saw was that there was quite a lot of glycogen accumulation right from the tongue, right up to the rectum in this mouse model of Pompe disease. And so looked at histology. There is glycogen accumulation.

There was cellular changes, but the mouse is not the patient. But what we did say is can we now try and see what the impact of enzyme therapy is, if any? And if there is an impact of starting early or treating at a more aggressive dose. And so we did a short-term ERT in the mouse model, and we did long-term ERT in the same mouse model. So in one, we started them at a slightly older age when the mice were three months of age, and what we saw was that there was just a partial clearance of glycogen. However, when you started early, so less involvement, we were able to get some clearance of glycogen. Of course, this is all first generation enzyme therapy. And the goal is that we learn from these lessons and from the patients as we get new therapies on the horizon to start to address these issues. So the recommendations here is we do now use this PROMIS-GI scale.

We do involve a gastroenterologist early for symptomatic management, and we are trying to look at what next generation therapies can do. And so I also want to state that there are a range of other unmet needs we try and hear and listen. And so for any patients in the room, always feel free to share with any one of us. We do take that seriously. We do try and look into it, and we do try and see what else we can do. And so in closing, this is that survey that I think Dr. Mozaffar already talked about. Clearly our patients are troopers. They continue to fill out surveys, they continue to teach us. But overall, they are fairly satisfied with their treatment. But yes, they do talk about unmet needs. They do talk about impacts on quality of life, impacts on breathing, pain, as was just talked about by Dr. Schoser. And so my take home message really is it is a continuous process involving all stakeholders, including the mice who also teach us and including the patients and all our collaborators, and learning from neurologists, pain specialists and everyone. Thank you. - We have some first questions here coming along.

So please, you are well aware you have here the code. So Priya, how has LOPD changed in the past decades? What change do you expect for the coming years? - I think a lot has changed, and there's a lot of progress. There's a lot of new hope, and I know there's still some line of thinking about newborn screening, but as I have started seeing this now, I have been wrong. I have missed patients for years. A number of children who were called lazy, who were called kids with developmental delay really do have features of the condition. So I think we've definitely changed there. I think we've definitely changed in so many therapeutic strategies that are now available for patients with Pompe. And I think there also is a lot more expertise around so many disciplines in the care of patients with Pompe disease. But I want to leave with one note. It doesn't mean that if you start treatment early that you're gonna plateau and decline. I think that's the message.

You treat early and you will continue to make progress, because you are not at that threshold point, you know, where there's such a lot of glycogen accumulation that you're trying to play catch up. And I think that's the message I really wanna give that we hope that there's a continuous improvement in patients with timely intervention. - Yeah, along this line, there's a second question on this. So this goes to Tahseen. So this inclusion of Pompe disease, and we both guessed that RUSP means newborn screening. We're not completely aware what is the abbreviation is. So is the expectation that the diagnostic delays is going down, Tahseen? - Sure. So as you're aware, newborn screening for Pompe is now in effect in majority of states in the US, and then some of the European states are starting to roll it out as well. It definitely does increase your chances of picking up Pompe disease at newborn screening.

The challenge is that 90% almost of the kids being picked up with Pompe disease have the late onset variant. And then the other challenge is we still don't know when the disease will manifest. We still don't know what's the best or optimal time to treatment. And as Dr. Kishnani mentioned it a few days ago, there are newer phenotypes that we are discovering, or new sort of disease patterns that we are discovering in these thing. The bigger challenge is we really have no way, we have no biomarkers to follow progressive glycogen deposition. So these kids are usually asymptomatic, although some of them may have symptoms, but most of them are asymptomatic. But how do we know that they're not progressively accumulating glycogen? And ultimately that glycogen will. So the holy grail here is can we detect disease earlier? Similar to what's being done in Alzheimer's, it is similar to what's being done in some of the other diseases where you have biomarkers, like amyloid imaging, or in MS, you have plaque sort of density that you can look at. We need something in Pompe that can estimate the muscle glycogen, we can follow it longitudinally, and that becomes our marker for disease response, et cetera. But yes, we've solved the problem of picking up kids with Pompe disease who will ultimately become late onset patients with Pompe disease. But how we follow them, who's gonna follow them, how do we monitor their disease progression still is something that we still have to come to terms with, and it's an area of active research. - So perhaps to both of you along these lines, it is not a question here from the audience, but for myself, so. Could ultrasound of the muscle, MRI of the muscle, could that be a way out at least?

Or is this something we need to explore? Or is there something more important? So there's some new techniques around, what do you think? - So again, right now the muscle MRI cannot pick up glycogen, right? That's one of the limitations. And muscle MRI is really good at looking at fat replacement, but we don't want to get to that stage. We want to pick it up before the muscles become fat. There is a group that has developed this technique, and I don't have experience with it. Actually I've heard Dr. Schoser's name being thrown around for that, where this ultrasound based technology can look at muscle fibrosis but also pick up glycogen. And I was gonna ask you earlier today, because they said that they have collaborated with your group. - Could I comment on this? Because we have used, and I didn't pay you for this, but thank you for that feed in. I still do think that even our traditional biomarkers are helping us. There is subgroups of patients with late onset Pompe disease that have really high CKs, like 800, 900. They have high ASDs, and some of them have the HEX4 at the upper limits of normal.

I actually think the HEX4 is a very good marker for separating IOPD from LOPD, but also it's telling us that maybe we're capturing the disease in time before there's extra lysosomal glycogen, at which point- - You can't do, yeah. - The ship has sailed. And so to that point, we actually collaborated with Lisa Hobson-Webb, who's our neuromuscular colleague, and we've used quantitative muscle ultrasound. It takes all of 10 to 15 minutes. It can be done in a baby, no sedation needed. And we've actually been using echo intensity and looking at the mean echo intensity, and I can tell you that what we have seen is that in patients who've got these increasing trends of biomarkers, the echo intensity increases. The pattern of involvement is what we see in adults with late onset, with the paraspinals, with the glutes, so, with the gastrocs, et cetera. So we are definitely learning that. And I think the other part which has been more reassuring is the kinematic findings where you need a wonderful PT to work on it. But then on ERT, you actually see the echo intensity coming down, you see the other biomarkers coming down, and you see the kinematics improving. So I do think that it's a new approach to management of patients, and it's a self-realization for me. It's a humbling experience for me where now I think calling them late onset does not mean that they are really late onset, and having the IVS splice site does not mean that it's fully protective, it's cardioprotective, it may not be muscle protective, and that there is this earlier phenotype.

And if we look at clinical literature, you'll see tonnes of papers of clinically diagnosed cases with LOPD, with the IVS splice site, who were picked up at two years and picked up at three years, so clearly they do exist, right, so. - Yep, yep. I think that that is one of the major learnings of the past two, three years. And we will, so as usual, treating rare diseases, relearning rare disease, and if we now start to have a newborn screening and see really early cases what we normally wouldn't have ever, they would not come to clinic because, well, they're so limited in the clinical symptomatic, but you can pick up it with the ultrasound, and ultrasound in the infants is a super tool. In the adults, it's more unpredictable. So, there's already, there I definitely would go for the MRI. And the new techniques we have in hand, we need to have to get more experience in this. So also this works for infants very nicely. So in Duchenne, there's nice studies done on this, but if it's a good tool for Pompe disease, yeah, there's first papers on this, but I'm not completely sure that this is already there. And it's, well, it's a laser device, so you need to have a special unit for this and things like that. So, it's not that straightforward and easy like an ultrasound. Consider with an iPhone and just a scanner, you can do it here immediately. So, it's now so handsome and so easy, you don't need these big ultrasound machines. So, it's really a bedside tool in a way, what we can use, and we should explore this better, and I fully agree on this. But there's some more questions here. Since it's such a progressive disease, how can we prepare patients for the changes in their condition? And this is in a way taking up a part of this shared decision.

So how can we really be in this dialogue with the patient and give them a feedback? - I would say- - Tahseen, I address this to you. - Yeah, I think- - To avoid that I have to comment this. - In the clinic when you see them, and especially we tend to see them in our multidisciplinary clinic, I think it's very important to counsel them. Counsel them on what things we are looking for, what complications we are looking for. And it really is one, again, as Benedikt said, it's a shared decision making, but we also need to build up a multidisciplinary team. So in addition to physical therapist and respiratory therapist and nutritionist, et cetera, we need to have gastroenterologists who have an interest in it, we have to have cardiologists an interest in it. And at some point, these patients may need to see these specialists as well, and which I think it's somewhere related to the second question that we are gonna come to as well. But there has to be a dialogue with the patient, why are we following you so closely? Why are we doing all these tests? These are the potential complications that may happen. We want to stay on top of it.

And again, as Dr. Kishnani mentioned, the biggest goal is we want to treat the glycogen before it becomes extralysosomal. Once outta the lysosome, it's gonna be incredibly difficult to treat that disease. So we want to monitor, catch them early, and that's why the early diagnosis is important. That's why early institution of treatment is important, but we also need to stay on top of the complications of it. - Comment from my side on this is still what we don't have, and we should go for this really as experts together with the patient, share this with the patient community is really defining standard of care. So we still don't have that. We have this for other diseases, and this was quite helpful. It's an approach, it's always a work in progress, because we learn new things and then we have to adopt. But this is something we need to do. And by this, we could better prepare patients for their changes and alert them, so that they come to us, so that they really say, "Well, there's a change and I need your help. So what can we do? What type of extra treatment can I have?" I think that's super important.

- Sounds like a great ENMC workshop idea. - Yeah, definitely. Another long weekend for all of us. - Yeah, that's fine. - That's good. And along this line, there's also a very good question. So, how can we address this with our colleagues? So we are metabolic and neuromuscular specialists here, and of course have a good background in genetics as well. But of course, we need to build up the community a bit better. We have in all the places some colleagues where we get help, but it's not everywhere the situation. So a lot of centres, they just have a neuromuscular metabolic specialist, but not someone else who is very good in GI and is super good in the understanding of the cardiac issue in some of the patients. So therefore this is something we need to do and to care locally a bit better for this to improve the quality of. And as centres, we should have interdisciplinary team, of course. And the final question I have here is, this goes to the super talk of Priya on the GI tract. So if GI symptoms are associated with infusion, did you implement any ERT regime changes?

- No, the point I was trying to make is that sometimes, it could be related to an enzyme, and on those days, the patients are just a little bit more careful with what they're eating, et cetera. My point was we've gotta look at other reasons. I had a patient who also had celiac disease and also had Pompe. But also to recognise that it can be part of the Pompe spectrum, and how do you really best address it. And I can tell you that as we moved some patients from first generation to next generation therapy, or when we increased the dose of enzyme therapy, some of their symptoms have improved, especially the incontinence in the paediatric patients did improve. And similar to that, like, you know, looking at ptosis or weakness of the eyes, not able to read as much, it got added as an additional endpoint in many comment, and showed that that had improved.

So I think next generation therapies with better targeting can help. Is it the solution? I don't know. But as far as IARs, sometimes you've got to manage it on a case by case basis, what is the trigger? Or don't eat certain foods, or know that this is occurring. So don't please eat corn on that day when you're getting your infusion, et cetera. - Okay, and by this, thanks for joining us here and hope you have some new insights to this still ongoing learning of Pompe disease. We all have, so it is really, we all do this now for, well, more 20, 25, 30 years, and we still see new facets. So, that's the interesting in our learning here, so that's why we thought it's good to bring up all these extra topics and not the mainstream that is normally presented. And of course, please have the evaluation and receive your credits for this. And thanks for joining us this evening.

Developed independently by EPG Health, which received educational funding from Amicus Therapeutics, Inc. awarded to EPG Health to help provide its healthcare professional members with access to the highest quality medical and scientific information, education and associated relevant content.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Amedco LLC and MEDTHORITY. Amedco LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Amedco Joint Accreditation #4008163.

Professions in scope for this activity are listed below.

Physicians

Amedco LLC designates this live activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.